Steven Soderbergh has one of the most unique, diverse filmographies of any director in history, as he loves to alternate between big Hollywood movies and much smaller, more experimental independent works. Soderbergh was one of the kings of independent cinema throughout the 1990s and while most of his films were generally well-received by critics, he never got to direct a real commercial box office success until 2000 when he enjoyed one of the finest years a director could ever hope to experience. He wound up directing two big box office hits, Erin Brockovich and Traffic, and pulled off the remarkable achievement of having both his films get nominated for “Best Picture” at the Academy Awards in the same year. He also got two separate nominations in the “Best Director” category for both films and managed to take home the award for his work on Traffic. Afterward, he directed the mega-blockbuster, Ocean’s Eleven, and the financial success of that film and its two sequels has given Soderbergh the freedom to continue directing low-budget, unconventional films like Bubble and The Girlfriend Experience, projects which may not make a lot of money, but personally interest him. In 1999, he directed a great little unconventional crime film called The Limey, which unfortunately, kind of got lost in the shuffle amidst Soderbergh’s subsequent success. The Limey is one of those films that may not seem like much on paper, but can turn into something special in the hands of a great director.

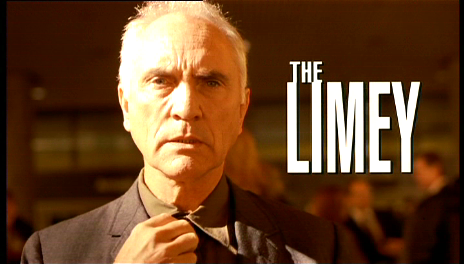

The Limey is a unique look at how an individual you’d normally see in a 1960s British crime thriller would function in the modern world. The main character is Wilson (Terence Stamp), a career criminal who speaks with a thick Cockney accent and has just been released from a British prison after serving nine years for armed robbery. After receiving news that his daughter, Jenny (Melissa George), has died in a suspicious car accident, Wilson instantly flies over to Los Angeles to find out the truth behind her death. Before he even finds out anything, however, Wilson has pretty much already made up his mind that she was murdered and that he wants to seek revenge. After meeting Ed (Luis Guzman) and Elaine (Lesley Ann Warren), two of Jenny’s friends from acting school, Wilson learns that his daughter was romantically involved with wealthy record producer named Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda). Wilson immediately discovers that Valentine was involved in drug trafficking and decides that he’s going to kill him to avenge his daughter’s death even though there doesn’t seem to be any hard evidence that Valentine was responsible. Wilson’s reckless badass personality is beautifully established in a fantastic early scene where he goes on a violent rampage and takes out Valentine’s drug-dealing contacts in a matter of seconds.

Now, before I talk about the stylistic filmmaking techniques used in The Limey, I should briefly discuss the DVD commentary track of the film by Soderbergh and his screenwriter, Lem Dobbs (who also wrote one of Soderbergh’s earlier films, Kafka). While 99.9 % of the commentary tracks out there involve people kissing each other’s asses, the commentary for The Limey involves a surprising amount of arguments and disagreements, as Dobbs was clearly not happy with some of the stylistic choices Soderbergh made when bringing his script to the screen. I gotta say, Dobbs comes across as a bit of a dick and I certainly take Soderbergh’s side on most of the issues. On paper, Dobbs’ script likely resembles a pretty standard revenge thriller and if a less capable director had filmed it in a straightforward, conventional fashion, The Limey might have been lucky to secure a direct-to-video release. However, Soderbergh uses a lot of inventive and clever filmmaking techniques to help elevate the material. The Limey has some of the most creative and unorthodox editing I’ve ever seen in a film, which helps turn some routine sequences into something special. Soderbergh’s most ingenious idea was securing the rights to use footage from a 1967 British crime drama called Poor Cow, which also starred Terence Stamp. When Wilson is talking about events from his past, The Limey uses scenes from Poor Cow as flashback footage with the much younger version of Terence Stamp representing the younger version of Wilson.

The Limey contains quite a few non-linear scenes that involve multiple uses of flashbacks and flash-forwards. You’ll sometimes see two characters engaged in a conversation in one location, and the film will suddenly cut away to the same two characters continuing their conversation in enitrely different location. Sound from one scene will often bleed into another and you’ll hear different passages of dialogue from different sections of the film juxtaposed into the present scene you are watching. The character of Terry Valentine practically gets his own trailer, as footage of him from various sections of the film is shown right before he has his first official introductory scene. And, of course, the film will often randomly cut away to footage of Wilson sitting on a plane, which turns out to be the key moment in the story. These editing tricks give the film a neat dream-like atmosphere, which enlivens what otherwise might be dry exposition scenes. The interweaving of the past and present make these sequences resemble a pieced-together memory. However, what really elevates the material and prevents The Limey from being nothing more than an exercise in style is the dynamite lead performance of Terence Stamp. The actor just fills every scene he’s in with amazing energy and intensity and he is clearly having a ball speaking in his over-the-top Cockney accent (which, incidentally, is a lot more convincing than the one Don Cheadle had in Ocean’s Eleven). One of Stamp’s standout scenes in this hilarious confrontation with a DEA agent (Bill Duke), who caps things off with one of my all-time favourite lines of dialogue.

Of course, Stamp also takes what could have been a fairly cartoonish character and invests him with a lot of genuine pathos. It’s obvious that Wilson feels great guilt about being locked up in prison and not being there for his daughter, and thinks that getting revenge for her death will help compensate for everything. The Limey follows the same formula as other revenge thrillers like Point Blank and Get Carter, where the main character is obsessed with their personal quest for revenge, but once they achieve their goal, what else is left for them? The film does address this very issue near the end and Stamp’s understated acting during those scenes is just marvelous. Because of its non-linear storytelling and editing, The Limey is one of those films that can watch multiple times and discover something new every single time. The film has been described as an “art-house Death Wish“, so those who watch it expecting a standard violent revenge thriller may be disappointed, and that’s probably why The Limey has never reached a wide audience. It received its fair share of critical acclaim, but didn’t make a dent at the box office and was completely ignored at Oscar time. Once Soderbergh achieved mainstream success with Erin Brockovich, Traffic and Ocean’s Eleven, The Limey became nothing more than a brief footnote in his career and was largely forgotten about. However, The Limey is definitley a “must-see” for those who are interested in the art of filmmaking, as it brilliantly demonstrates how masterful direction, editing and acting can take a script and elevate it from B-movie status into a deep, multi-layered piece of work.