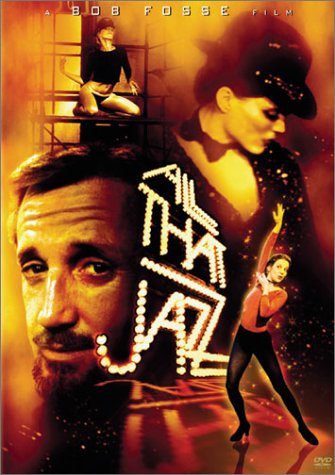

Warts-and-all biopics are rarely given full breadth by the subject themselves but Bob Fosse defrocked himself of all aggrandizement and his gift of disclosure was All That Jazz. It’s a blazing crowning achievement from the Broadway director who channels his neuroses, peccadillos and egotism through the fictional theater impresario Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider).

Fosse isn’t very flattering towards his alter-ego’s latest projects. The funding committee behind his show yawn in disapproval over his choices and his editors bemoan his non-judicious editing of The Stand-Up, his introductory Hollywood film. He is verging on self-destruction and collapsing under the pressure of expectations. Harry Nilsson’s dejected song “Perfect Day” plays over Gideon’s nirvanic seduction of a young actress and both he and the audience are omniscient that it’s a vacuous example of exploitation on his part.

The reveries of Joe’s foggy, spectral conversations with the “angel of death” (Jessica Lange) ride the razor’s edge of pretentiousness. But Fosse’s avant-garde artistry transcends the pitfalls for a rather meditative, interiorized confessional from Joe which predates JCVD in its self-deprecation.

Gideon hypocritically accuses his girlfriend of infidelity and his only defense is “I stay in with you”. Of course, when Katie mournfully says “I wish you were so generous with your cock”, Gideon seizes the moment as a eureka for one of his productions (“That’s good. I could that.”). Anyone in the creative field can relate to selfishly gerrymandering and pilfering from pain for their own endeavors.

Fans of Alf will be in stitches when Max Wright appears as Joshua Penn, one of the producers of Gideon’s movie and nearly has a conniption over the lengthy post-production sessions. His morning ritual of Dexedrine pills, cigarettes, Vivaldi and “it’s showtime” are a monotonous mantra which slowly fails to be an affirmation.

Anyone qualmish about musicals can rest their anxiety because the song-and-dance numbers are rehearsals for Gideon’s upcoming show until the spectacular ending. Skewering show biz folk as being vain and self-centered is not a revelation. What’s remarkable about All That Jazz is how Fosse captures the essence of how we are all Icarus who are reaching to the heavens for “perfection” (ala God’s creation of the rose) but are hardly satisfied with the results.

The film also isn’t tumid with self-seriousness. The hospital scenes have an underpinning of mortality around Joe’s angina but it is juggled with a spangly spirit. He told that he is “flirting with disaster” while he is promiscuously sleeping with ingenues for “exercise” purposes. Afterwards, during Gideon’s open-heart surgery, the pitch-black conversation about recouping costs if he expires, nudges the film closer to The Producers absurdism.

Many films like De-Lovely and later Beyond the Sea have gambled on the fourth-wall-breaking conceit of Gideon directing an ostentatious play version of their own story but he lacked Fosse’s edgy nerviness and flair. It could’ve easily been too precious but Fosse caps the film magnificently as Joe is ailing on his deathbed. For this reason, Scheider’s tour-de-force performance and sheer virtuosity, All That Jazz is staggeringly invasive, underappreciated toe-tapper.