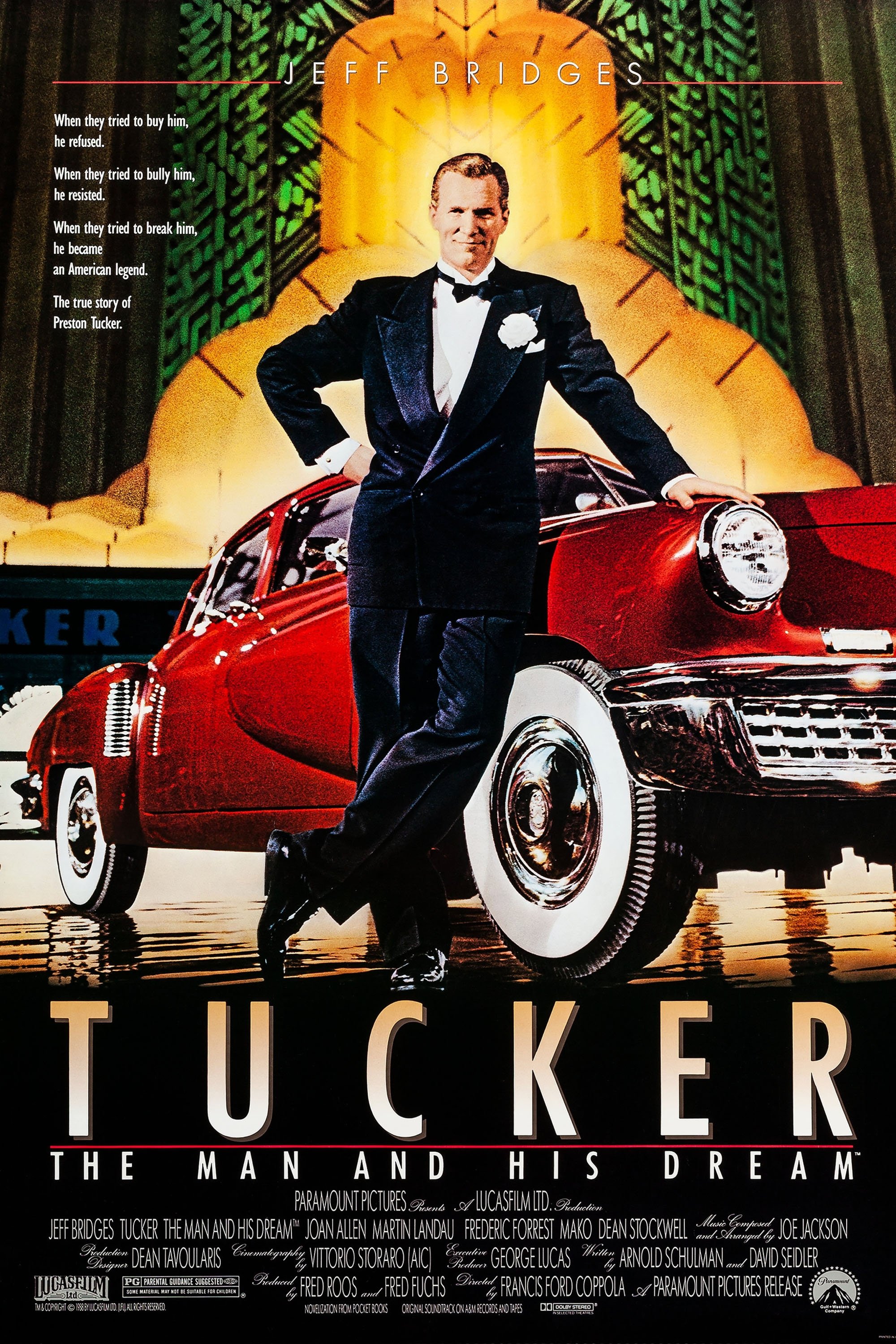

Rarely has a biopic about a disgraced vehicle magnate been so chipper, uplifting and halcyon. The American Zoetrope logo is an indication of the old-fashioned approach that Francis Ford Coppola is utilizing for his hugely engrossing portrait ‘Tucker: The Man and His Dream’. The whole movie is glazed in a honey-pigmented lens and it is as wildly Icarus-like as Preston Tucker (Jeff Bridges) was.

The altitude of Tucker’s visionary grandiosity is matched by Bridges’ sanguine performance. Ala William Randolph Hurst and Howard Hughes, Tucker was an entrepreneur ahead of his time. During the montage reel of Tucker’s exorbitant ambitions, his military tank was rejected because the 30-mph-plus velocity was deemed gratuitous.

Unlike the aforementioned titans, Tucker was unanimously scoffed at and investors in his project were infinitesimal. As a David-vs.-Goliath tale, Coppola doesn’t mollify the seemingly non-Capra-esque sentiment that occasionally folkloric heroes flounder when squabbling against the Big Three automobiles manufacturers. The sensationalistic 40’s-style narration by Bob Safford is a beautifully atavistic touch.

Even the Vittorio Storato cinematography is painstakingly spruce such as the phone conversations between Preston and his wife Vera (Joan Allen) where the camera dollies from one set to the other and then another one in which Vera is bas-relief in the foreground while he blusters in the background of a station. Bridges’ head is so permanently levitating in the clouds that he is willfully incorrigible towards his son, Preston Jr. (Christian Slater), who jettisons his Notre Dame acceptance to bask in myopic idealism next to his foolhardy father.

Other than the novelty of Tucker Sedans, the legacy of Preston’s benighted optimism was eternally tainted. For all his glee, Preston wasn’t immune to flights of irascible frustration such as when he pulverizes a blueprint before he is “given a ringside seat to [his] own crucifixion”. This aspect of Preston could be an eviscerating, exceeding-one’s-grasp self-critique by Coppola about how he parochially saunters onward despite the omnipotent odds otherwise.

The most nail-biting sequence is during a stage presentation in which Preston must prorogue the display until the backstage antics of a fluid leak are promptly remedied. What essentially sounds copacetic on paper is an abject fiasco in execution (the shareholder’s redesign of the rear engine is inarguably pragmatic but it is reproached with disdain by Preston’s goosesteppers) and that lesson reverberates continually through this saga.

For that reason, ‘Tucker: The Man and his Dream” is understandably an esoteric passion project for Coppola. But, in his pursuit of romanticism gone awry, he has yielded one of his snappiest, most hermetic and cheerfully luminescent pictures. Metal might oxidize and rust but Tucker’s riches-to-rags biopic will be everlasting.